2020-09-06

After a week off, I’m back. And there’s a ton of stuff to talk about.

Meme Marketing

This topic emerged from a conversation with my friend David Park. David’s company, Kippo, is a dating app for gamers. And while there’s much to talk about regarding the digitization of dating and social interaction, the company’s early growth strategy is amazing.

A few months ago, Lenny Rachitsky asked on Twitter:

Consumer app founders: How did you get your first 2,000 users?

To which David responded

Created a meme with a footer to our website. Made it to the front page with 52k upvotes. Free impressions

I finally got a chance to catch up with David last week and had to ask him about it. Here's a brief summary:

(One day, we'll need to get David to deconstruct this process some more, but for now, you're stuck with my rendition.)

Reddit is the self proclaimed "Front Page of the Internet". When successfully harnessed, Reddit can send your website a stampede of traffic. That's great for marketers, but Redditors HATE being marketed to. Perhaps due to unsavory past experiences, the moment they smell a marketer, Redditors attack. The visual I imagine is much like bees turning on their queen.

After spending far too much time on Reddit, David noticed that Memes outperformed other posts. He started asking: “How could we make memes work for Kippo?”

But he didn't just blindly start making Memes. Instead, he asked a pivotal follow up question “Why is a meme funny on Reddit?”

The Kippo team noticed patterns. Some memes were unexpectedly relatable. Others had shock value. And they got to work producing memes that reconstructed those sensations.

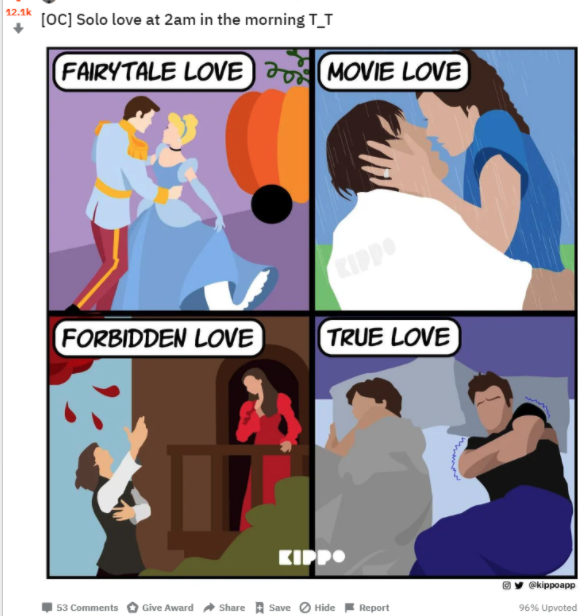

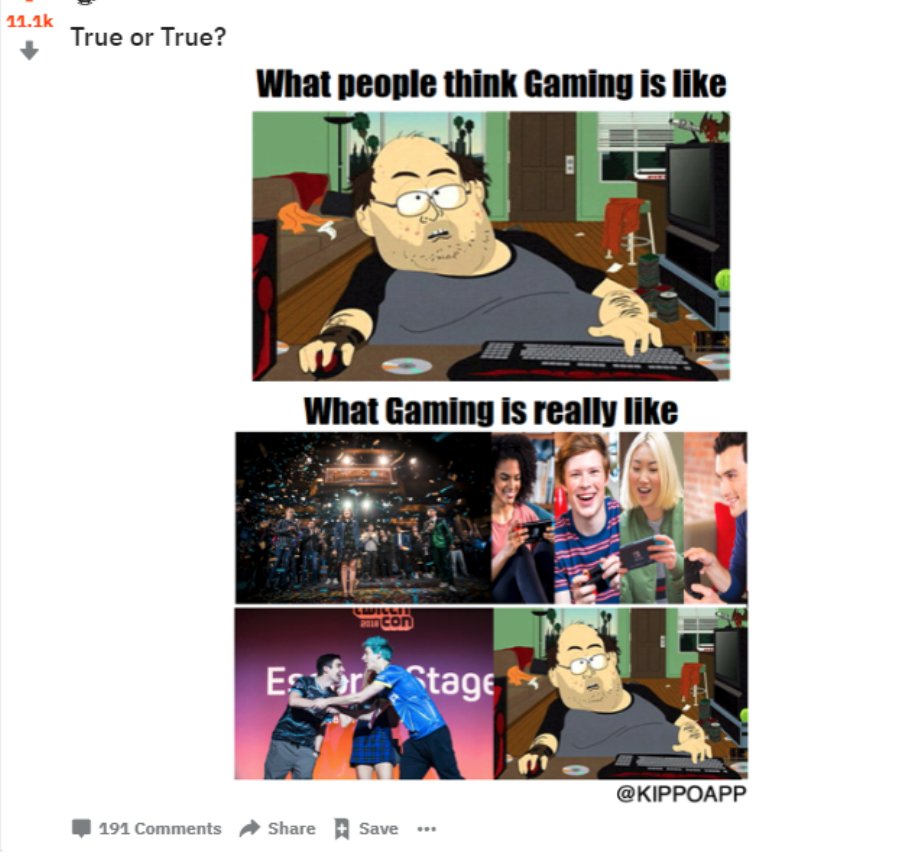

There were some duds, but soon enough the Memes started to catch fire. Here are a couple:

Kippo doesn’t rely on Memes as much these days (see Kippo Comics for their primary meme distribution channel), but I found this 0 to 2,000 users story fascinating. It reminds me of this grab-bag of tactics used by Kapwing - which is presumably, the maturation of tactics from Kapwing's early days of (successful) floundering. As well as this tactic used by Tower Paddle Boards to grow via Unsplash.

Unconventional, but very effective.

Open Source Business Models

Money and open source have a funny relationship.

First, let's clarify that there is no philosophical tension between Open Source and profits. The Free Software Foundation, arguably the spiritual center of Open Source, has this to say on the topic:

Many people believe that the spirit of the GNU Project is that you should not charge money for distributing copies of software, or that you should charge as little as possible—just enough to cover the cost. This is a misunderstanding.

Actually, we encourage people who redistribute free software to charge as much as they wish or can.

More fundamentally, there seems to be a contradiction in how to make money with Open Source. How do you charge money for software that is 100% open and free to run? Would that not yield perfect competition, eliminate profits, and turn these into untenable businesses?

Well, Red Hat (acq. by IBM), Cloudera, MuleSoft (acq. by SalesForce), MongoDB, and Elastic all beg to differ. These are all multi-billion dollar companies that trade (or traded) on the public markets.

And if you look at the IPO pipeline, you might see Confluent, Hashicorp, Databricks and others not too far away from the event horizon.

So what do these companies charge for? A survey in the history of enterprise open source will yield the following story:

- Support (i.e. Red Hat)

- Proprietary software built upon an open source core - aka Open Core - and sold as an annual license (i.e. most of Elastic's business)

- SaaS offering of the open source code, in partnership with public cloud (i.e., the fastest growing segment of Mongo's business)

For those who follow enterprise software, it's the SaaS angle that has recently unlocked Open Source for these venture backed businesses.

It's interesting that all of the examples I cited so far are very much "infrastructure" products. But the trend of Open Source business models has caught on elsewhere too.

Consider Mattermost (an Open source Slack alternative) and Ghost (an alternative to Wordpress). Two examples of how Open Source software is expanding beyond it's "home court" of developers, and capturing a broader spectrum of users. (Ghost, btw, is not only Open Source, but a non-profit too. One that just happens to make $200K+ in MRR)

And if you look at smaller products (yet admittedly, more targeted at developers), you might find TailwindUI, which is built atop the Open Source project TailwindCSS. Or Laravel Forge, which is similarly built atop the Open Source project Laravel

Without considering all these examples, you might have believed that there is no business model in open source. That the only way to get funds doing Open Source is getting backed by a corporate patron (ie React), or decentralized patronage (ie Vue). And for many (most?) open source maintainers, survival is indeed about finding patrons. (Choose one of: 1) GitHub sponsors/Open Collective, 2) work for Google/Facebook on Open Source, or 3) burnout).

But that's simply not the full story. Too many developers get into the "business" of Open Source without ever realizing that they're sitting atop a potential goldmine (in the form of a community and audience). Open Source maintainers are often influencers by accident. The challenge is monetizing this influence.

Open Source businesses are going to become increasingly important moving forward (especially for developer focused products). Open Source builds trust, transforms the community into "co-creators" (superfans), generates another distribution channel, establishes goodwill. A well run open source company has natural advantages that its closed source counterparts simply do not have.

This is not to say Open Source business is easy. Simply that it is the future.

I’ll be writing about this topic a lot, but just giving you a first glance into my mind.

Miscellaneous

I'm introducing a new section to these weekly notes, where I write bullet points about random things that I came across this week. If the above are half baked notes, the following are uncooked. Here we go:

- First thoughts on Rust-lang. Coming from Golang and Java, the idea of eliminating concurrency issues like race conditions by design is amazing. Sadly, I also miss Golang's compilation speeds. Go compiles fast by design

- I finally watched Be Water - the documentary on Bruce Lee. His unyielding refusal to take on any demeaning role, paired with a mentality of "your loss" towards those who didn't value his vision - is a model of self-respect. We lost Bruce when he was 32 and right on the cusp of superstardom. Far too early. And in a huge blow to Asian American masculinity, Hollywood picked Jackie Chan as his successor. I love Jackie, but - let me just say this, Jackie worked in the house, and Bruce in the field.

- Datadog is an amazing company - or at least I think it is, after looking at their 10K. Sales and Marketing efficiency is best in class. Their strategy is amazing too (unified metrics, tracing, and logs chefs kiss). So much to learn and unpack about this company.

- The next time you're scared and want to "bury your head in the sand", consider the facts. Ostriches do not actually bury their heads when scared. Rather, they bury their eggs in the sand, and rotate their eggs multiple times a day. They are not scared, they're just taking care of their young. I mean, just think about it, why would a 9 ft, 350 lb animal be scared? Not to mention they're fast (40 MPH, which is 10+ MPH faster than Usain Bolt). You've seen the Kevin Hart skit. Fear the Ostrich